They say—and I can attest to it—that a bad day of fishing is better than a good day in the office. I’ve heard the same thing about boating. But that’s where I draw the line.

A day of boating—no matter what kind—is never as good as a day of fishing, no matter how bad. And a bad day of boating is potentially the worst day of your life. Truth be told, boating is like being in jail with a chance to drown.

Here’s proof.

For more than 15 years, my childhood and high school buddies from Brooklyn—a half dozen septuagenarians who fancifully continue to self reference as “The Red Hill Gang”—have honored me by accepting an annual invitation for a weekend of fall surfcasting in Amagansett and Montauk. For the sake of fishing, they put aside their well-justified prejudices against my prickly personality, sarcastic social commentary, and obnoxiously compulsive penchant to correct their spelling, grammar and tortured syntax. As adolescents, we fished for flounder and eels and crabs and blowfish along the shores of Jamaica Bay, or from Steeplechase Pier in Coney Island. Our nostalgic reunions never fail to recall those bygone times. My bounteous cooking and miserable card playing contribute mightily to everyone’s enthusiasm. But the bottom line is we gather to fish. And sometimes we do stunningly well.

On Long Island’s east end, we cast and we reel and we catch bluefish and weakfish and striped bass. All from the beach. We hunt them and we chase them on foot, or riding the shoreline in my truck. If we enter the water it is barefoot and in bathing shorts—weather permitting; otherwise, boots and waterproof waders. We never leave terra firma.

However, for nearly as long as The Red Hill Gang has been reuniting on the beach in autumn, we also have gathered regularly for winter roadtrips. These jaunts have found us in Las Vegas, Florida, the Caribbean. There’d always be poker. Sometimes golf. Thoroughbred handicapping if there was a nearby racetrack where we could donate a couple of hundred bucks. And whenever we were in proximity to a sizable body of water, there’d be attempts to fish. Though that has always been open to interpretation.

PLAY FOR A DOLLAR: Always, there is poker.

Like the time in Puerto Rico when we spent more than six hours and well nigh a thousand dollars on a 40-foot luxury cabin cruiser searching the sea for big game. “The Cadillac of sportfishing boats,” we were assured. But we never encountered a single bite, and I was mystified that for all our trolling and sailing from one spot to another, there wasn’t a sign of another fishing vessel. When I asked the captain about this, he blithely replied, “Oh yes. They’re out there.” I rubbed my eyes, cleaned my sunglasses and looked again.

They are? Where? Short of ghost ships visible to him alone, not a ship was at sea. And not a fish did we catch.

The Red Hill Gang’s most recent winter escapade was to Islamorada in the Florida Keys this year, where all our usual antics played out amidst idyllic beaches, infinity-stretches of tropical waters, exotic birds and sea life, and nonstop margaritas, bloody marys and pina coladas. You want a floater with that? Why the hell not!

However, there were also boats. Two of them, purportedly for fishing. True, there were rods, reels, bait, nets and other piscatorial devices aboard. But for my money, those were mere distractions. They could not mask the truth. We were going boating.

We split into two groups of three passengers for each craft, which were piloted by veteran skippers. Captain John was a professional guide, knowledgeable of the local waters, if also a bit sketchy in his approach to maritime regulations. Did he really have the proper certification to fish in Everglades National Park waters? Was his 18-foot Dolphin Backcountry skiff properly outfitted with safety and navigational gear? When we first saw John’s low slung, nearly flat-bottomed open boat tied to the wharf, one of the guys turned and nearly bolted away. The port and starboard gunwales were barely a foot high and there wasn’t a boat rail anywhere. The skiff looked like a motorized surfboard.

But I gingerly stepped down to it, and we shoved off into the Florida Gulf for a rendezvous with the other Red Hill Gang trio. They were aboard a larger, 26-foot center console Pathfinder Bayboat, with Captain Ed at the helm. He wasn’t a certified captain or fishing guide; rather a professional colleague and friend of one of the boys, and an avid weekend boater. But Capt. Ed wasn’t having a very good week on the water. Just a few days before, his engine conked out and he had to be towed to back to the marina.

As Capt. John zipped us over tiny swells towards our meeting point, he received a phone call. Capt. Ed’s GPS navigation system was acting squirrelly. That didn’t sound good. Indeed, it turned out to be horrible. Without the GPS, it was impossible to precisely gauge the water depth, which was quite shallow in many spots of the Gulf. It also made it more challenging to follow the dredged channels, which was vital to avoid running aground.

So that is exactly what happened. Just inside the Everglades boundary, Capt. Ed missed a channel marker. Without his GPS providing a proper warning, he traversed through mere inches of water and his boat became mired in the mud.

Approaching this ugly scene, Capt. John instantly concluded we could offer little help. We didn’t dare get any closer than a few hundred yards for fear of running aground ourselves. So there was no way to toss a tow line over to Capt. Ed. Even if that was possible—I suggested they cast a fishing line to us so we could attach a rope they’d able to reel back to their boat—Capt. John’s skiff was not powerful enough to dislodge the other boat from the mud. The tide was dropping, not rising, so there was no chance that Mother Nature would solve the problem anytime soon. There was only one thing to do: call in Sea Tow, the private, nautical version of AAA.

Capt. John relayed the location coordinates since only his GPS was online. Capt. Ed made the arrangements via cellphone. It would be hours before someone could get out to him. We hung around for a few minutes, but the scene was maudlin. The guys aboard Captain Ed’s boat were as helpless as we were. I thought they should at least toss a few fishing casts. But Captain Ed’s prideful brooding put the kibosh on that.

With no way to further assist, Capt. John moved his skiff off to a few of his favorite nearby fishing holes, hoping to salvage something of the day for at least half of us. For the next few hours, we flicked our lines baited with live shrimp into the shady waters that edged hauntingly still and silent mangrove islands. The net result was that a lot of undersized, caught-and-released mangrove snappers ate very very well that morning—and we got seriously sunburned.

When Capt. Ed informed us that Sea Tow was fast approaching, we hurried back to the scene. And not a moment too soon. The Sea Tow pilot was coming up on Capt. Ed’s marooned boat in perilously shallow water himself. “You’d better change course, now,” Capt. John warned. The Sea Tow captain looked incredulous. But Capt. John scolded him again. This time, more stridently. “You see those channel markers over there? That’s where the channel is!” John barked. The Sea Tow boat then took a new approach.

But the rigamarole wasn’t over yet. Because they were in Everglades Park waters, Sea Tow could not do the extraction without clearance from Federal Park Rangers. So, another couple of hours delay ensued. Well beyond the time limit of our half day charter, and having zero desire for a run in with anyone of an official capacity, Capt. John wasted no time bidding Captain Ed farewell and good luck before the Park police arrived. We sped away from our stranded colleagues and the clueless Sea Tow driver, returning to the dock.

The afternoon sun had begun to descend by the time the Red Hill Gang was fully reunited at the marina’s tiki bar. Over a couple of rounds of cocktails—don’t spare the floaters, thank you—the final act of Capt. Ed’s sea saga was recounted. He eventually had to climb over the side and slosh his way through water with a bottom consistency of reedy mayonnaise in order to retrieve the tow rope from the Sea Tow craft, which could not approach any closer than we were able hours earlier. Then the Federales boarded Capt. Ed’s boat, inspected every nook and cranny, interrogated all on board, and fined Capt. Ed. for the infraction of not having a whistle.

Really? A Whistle?

It might have made the day’s misfortunes all worthwhile, had Ed taken that opportunity to evoke Lauren Bacall’s immortal lines. But Capt. Ed wasn’t quite cheeky enough to suggest to a pair of armed authorities: “put your lips together and blow.”

“But he’ll have the GPS fixed by tomorrow” one of the gang reported. “So we’ll be able to head out fishing again same time, same place, in the morning.”

“Boating,” I corrected. “It is not fishing. It is boating!”

And no good can come of it.

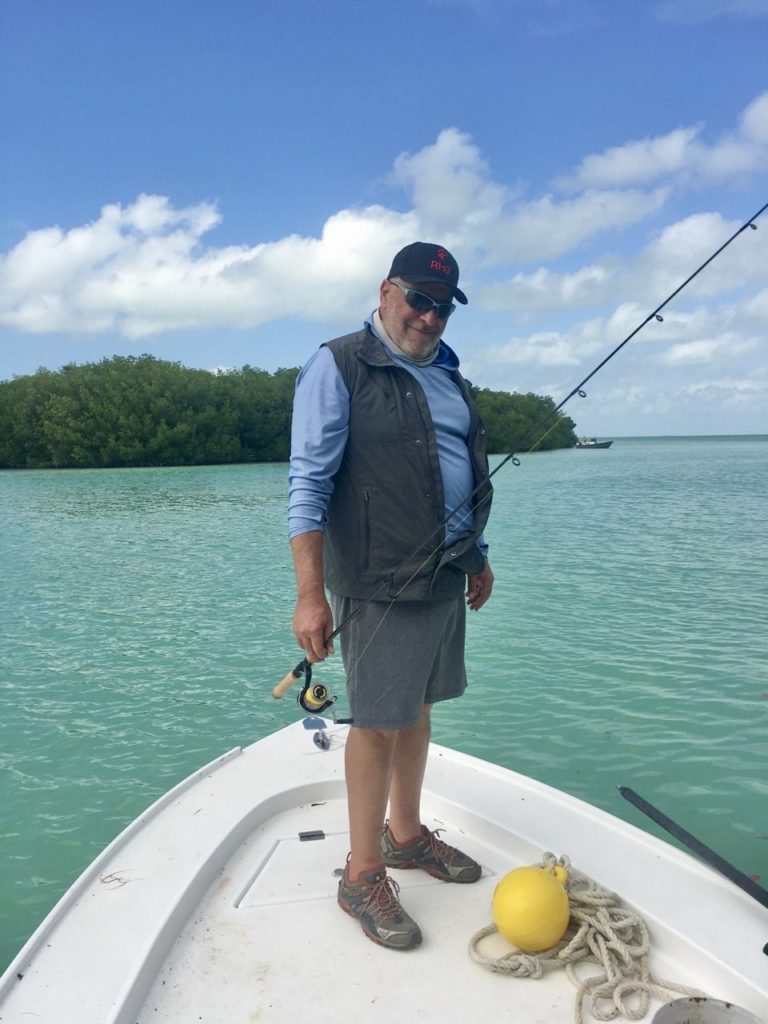

BESTIES: Doing What We Do Best